Framing Your Goals to Inspire Action

How to Write What You Want (So You Actually Get It!)

If you’ve spent any time reading about productivity, you have (no doubt) heard of SMART Goals. Like most productivity advice, SMART Goals are frequently prescribed but rarely implemented.

Inquiries about goal setting remind me of guessing the teacher’s password in grade school — parroting back a memorized answer of “make them SMART!” without any real understanding of what that actually means. No two productivity writers can agree on what the mnemonic label S-M-A-R-T actually stands for.

For our purposes, SMART Goals will refer to goals which are Specific, Measurable, Actionable, Rewarding, and Time-Based.

Writing down our goals forces us to clarify what we want and provides filters for opportunities. Why write them down? Simply writing down your goals, even without telling a single person, will increase your chances of achieving them by 50%. You can increase your chances further if you also build in accountability from a friend.

I do not even count a goal as real until it has been written down. Our thoughts are in constant danger of being overwritten, but we cannot deny the existence of what is on the page right in front of us.

My use of the word “framing” in the title is very intentional. Frames are funny things. In a paper I found incredibly influential, Simeon Dreyfuss summarizes the phenomenon of frames:

I like to think of this human impulse towards order as a kind of window frame: It helps us to make sense of what we are looking at, but our attention must always be on what’s on the other side of the window, not the frames themselves, which after all tend to exclude more of the total vista than they include. Those photographers among us know well this struggle to construct partial or provisional meaning through what is included or excluded from the frame.

~ Something Essential About Interdisciplinary Thinking, [my notes]

Similar to goals, frames are false boundaries to make sense of a messy world. They are useful abstractions, but like the borders on a map, they are not to be confused with the territory itself.

Our goals are meant to serve us, not the other way around. We have the power to frame our goals in whichever way inspires us the most. When our goals no longer serve us, we rewrite them, rewriting our own utility functions in the process.

We use goals as a simplified model for our behavior. Goals represent progress towards “success”, however you define it, but we never mistake goals for progress or for success itself. As with a window frame or a photographer’s lens, we purposefully put blinders on, hiding what is outside the frame of our goals to force our limited attention upon them.

Framing improves our signal-to-noise ratio through the removal of unnecessary context. Our ability to focus is automatically improved as our attention is spread among fewer objects, each with a higher average importance.

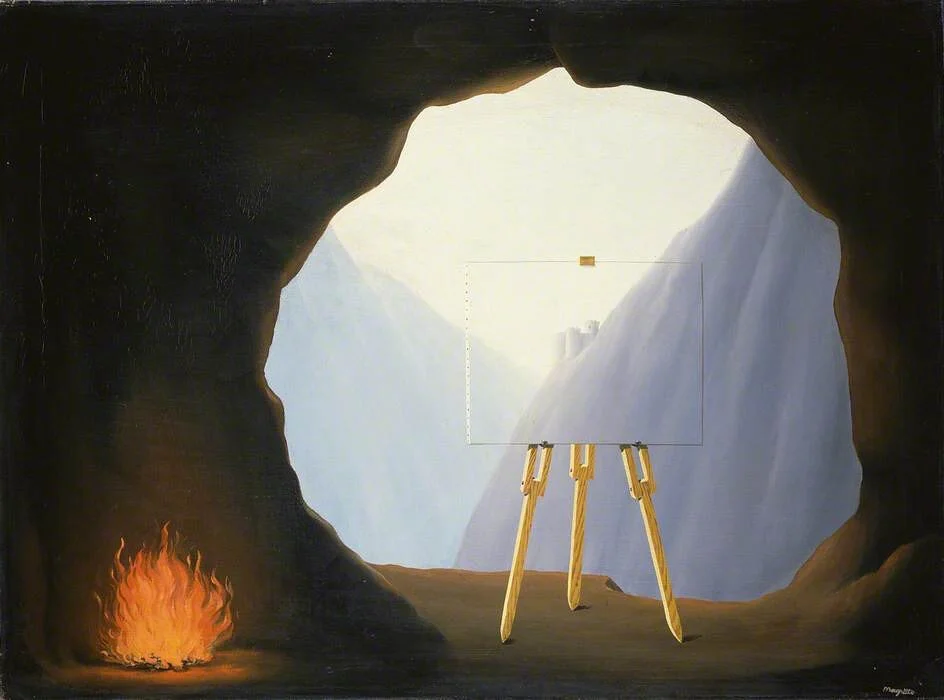

René Magritte, “The Human Condition.”

With that introduction in mind, let’s now get our hands dirty.

I will now summarize the latest science-based reasoning for why your goals should meet these five criteria. I will also give brief examples for each to illustrate proper implementation.

Specific goals have consistently been found to be more effective.

The more specific you can make your goal, the more you will persist through the undermining effects of anxiety, disappointment, and frustration.

If a goal is specific, it will have clear, binary (1/0) success criteria. We will either be successful in completing our goal or we will fall short. There is no grey area.

We avoid giving ourselves wiggle room by aiming towards a clear goal. Wiggle room is like a leak in a ship. Slowly but surely, your days take on water, accumulating technical debt until you’re forced to abandon ship and rebuild your structure anew.

Visualize how your life will look when your goal has been achieved. Compare that image to what your life looks like right now. Add these relevant differences to your goal and begin creating your roadmap towards achievement.

NOT SPECIFIC

I will be a highly paid public speaker.

SMART

I will give five presentations in 2017 where I am paid over $10,000 each.

We measure results to determine whether a goal has been achieved, as well as track progress along the way.

On the other hand, without the feedback that measurement brings, you are unlikely to make any progress on your goal at all.

In my experience, the awareness that comes from measuring an aspect of your life is enough to bring about improvement on its own. To change your time, diet, sleep, or spending habits simply start measuring your current behavior.

NOT MEASURABLE

I will improve my diet and exercise.

SMART

For the next 30 days, I will log my food and track my workouts, eating from a pre-determined list of Paleo options and weight-training at my gym for 60 minutes every M/W/F.

Actionability refers to how closely our goals are tied to our own actions.

Actionable goals remove noisy data from luck and external points of failure, allowing us to concentrate on the elements within our locus of control. Our motivation is the highest when we have internal coherence: when the short-term actions we take are closely tied to our long-term goals.

Actionable goals are tied to our process rather than the intended outcome, and use lead measures rather than lag measures. Lead measures are the inputs which produce results, while lag measures are the result of earlier action. Sales is an example of a lag measure: an outcome dependent on outside factors. The number of sales calls we make is an example of a lead measure: a process that will reliably lead to sales down the line.

To make a goal actionable, work backwards by listing the actions necessary to reach your intended outcome.

NOT ACTIONABLE

I will sign 10 new clients in Q3.

SMART

I will reach out to 60 potential clients and set up 20 consultation calls in Q3. [Assuming 1 in 3 leads convert to call and 1 in 2 calls lead to contracts]

Rewarding goals are sufficiently challenging and personally meaningful.

In the much heralded state of flow, full engagement is most often achieved by raising the bar. Counterintuitively, increasing reward means making the goal more difficult rather than more achievable. A large meta-analysis showed that goal level correlated strongly with learning: the more challenging the goal, the more learning that took place.

Ask yourself — why is this goal important to you? Having a strong reason behind your efforts increases self-efficacy and builds the sustainable intrinsic motivation necessary to persist through rough patches.

There is nothing quite like the clarity and momentum that comes from full commitment to a challenging and personally worthwhile goal. You will know you have one when even the possibility of achieving it fills you with excitement.

NOT REWARDING

I will file my taxes on time this year.

SMART

I will have full records of all my earnings and a categorization of every business and personal expense over $50. Full transparency into my finances will allow me to automatically identify opportunities to earn and spend more effectively. This in turn will allow me to work less, opening up time and freedom to pursue my own interests.

Time-based goals have a definitive endpoint. Without a deadline, a goal could potentially stretch on forever and thus have no possibility of failure.

Having a delivery date is the forcing function that emphasizes completion over perfection. The ideal is to strategically combine long-term and short-term goals — long-term goals to inspire and short-term goals as checkpoints to build success spirals of confidence.

Having an endpoint set in advance eliminates much of the internal friction associated with getting started. I am confident that anyone reading this has experienced the quagmire of analysis paralysis. Constantly questioning the desirability of the current goal will quickly reach diminishing and negative returns.

The only way I have found to subvert my tendency to delay commitment is to treat my life as a series of closed experiments. I have found that a 90 day time-period is sufficient time to test all my assumptions.

90 days is only 1% of the way to my 25 year goals. All moon-shot goals become approachable with this framing of “what can I do now to get 1% of the way there?” Even if I fail on paper, I can frame my experiments so that the inevitable learning eliminates the possibility of regret.

If 90 days feels too aversive, focusing on a single goal for as little as 30 days can tell you enough to determine whether to commit further.

NOT TIME-BASED

I will launch my own startup.

SMART

In the next 30 days, I will work on my startup [specify which activities count] for a minimum of 20 hours per week. I will determine whether it has product-market fit by interviewing potential customers to identify pain points, signing at least one customer to a paid contract. I will take objective measures of my life satisfaction along the way to determine whether this is how I would like to spend my days moving forward.

• • •

It is critical that you have empathy for your future self by separating the planning of your goals from the execution of them.

Once your experiment is planned, focus on daily execution. Afterwards, you can give yourself permission to change or even abandon the goal completely. Just make sure that you commit to giving your best effort for the full 30 or 90 days.

The existential anxiety that plagued me in my past has disappeared with the self-assurance that any goal is but a temporary path. I simply try to give all my experiments the full opportunity to run their course. All of my major career jumps and most valuable habits are a direct result of successful mini-experiments that I have continued to expand upon.

• • •

Have you actually taken the time to think about your goals? If you have, congratulations! You now have a much better idea of what you want in life. If you have been particularly introspective, you will even have some clear, actionable steps to take.

If you have just been reading along, patting yourself on the back, I highly recommend you take the time now to reflect. The whole point of this is to do the exercises — reading alone will not get you anywhere.

In the following chapters, I will walk you through my approach to making your goals a reality. You will get orders of magnitude more value from my advice if you already have your goals in mind.

Special thanks to Marianna Phillips for editing and to Rob Filardo for reading an earlier version.